What Did You Call Me?

An incarcerated person writes about how dehumanizing language like “inmate” is destructive.

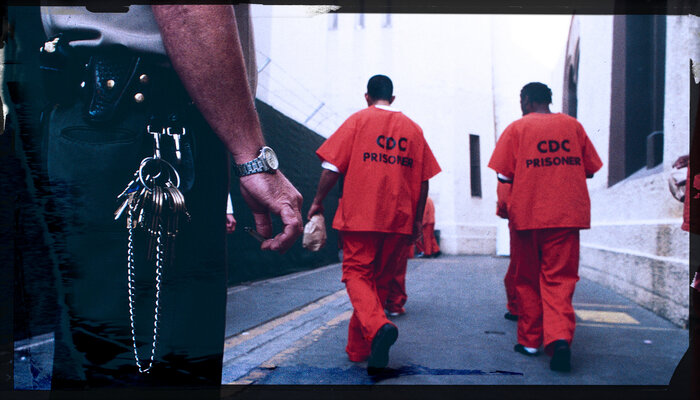

This essay is part of the Brennan Center’s series examining the punitive excess that has come to define America’s criminal legal system.

It all starts with a label. Nazi Germany, Rwanda, and American slavery all hold that in common. In each case, targeted groups were assigned names that had the psychological effect of dehumanizing. Once you’re not seen as a human, you don’t see yourself as human — and inhuman treatment begins that could cause your end.

Mass incarceration started with labels, too. The n-word accompanied the Black Code laws that returned freed slaves to plantations to work the fields, unpaid (under “convict leasing” schemes) for minor, often made-up offenses like vagrancy or not signing a labor contract with a white plantation owner. Under Nixon, when it had become politically inconvenient to call Black people the n-word, they called us “criminals” and proceeded to build prisons focused on punishment instead of rehabilitation to discipline behavior born of oppression and intergenerational trauma, rather than offering reparations or healing. The tag “super-predators” launched the locking up of kids, sentencing teenagers to multiple life terms, then housing them in adult institutions. One label ran alongside all the others and helped balloon the prison population in America to over 2.3 million. That term is “inmate.”

Webster’s defines “inmate” as “a person confined with others in a prison or mental institution.” But calling a person an inmate doesn’t describe where you are, it says who you are. It identifies you as your incarceration, as an outcast.

Not all labels are harmful, of course. Calling someone a student or a mother brings up positive images and reactions. Not so the word “inmate.”

With over 20 years in prison and counting, I hear correctional officers use the word constantly with an inflection in their voice that sounds like they’re talking about someone less than human. I remember a correctional officer giving a new CO a tour of the media center at San Quentin. “This is where the inmates record the ‘Ear Hustle’ podcast,” he said, meaning to express pride in what we did — but because of his use of the word “inmate,” what I heard in my mind was, “This is where the monkeys we trained record ‘Ear Hustle’.”

Correction officers are trained not to see us as human; it helps them do their jobs. They are trained to be able to pepper spray or even shoot us without warning, if it appears necessary. It helps them maintain that “professional” distance by seeing us as different from them, less than them, as “inmates.”

I think society must see people in correctional facilities as less than human as well. Even some social justice advocates and news reporters use “inmate” without regard for the damage it causes. I’ve seen incarcerated people internalize that word, lose touch with their personhood, and do nothing with their prison time but mop floors.

If you think that word is harmless, close your eyes and tell me what image comes to mind when you hear the word “inmate.”

Language is obviously important. Why do newspapers and even the California prison system respect the pronouns and language of the LGBTQ community? Why did news reporters stop calling undocumented immigrants “illegals”?

As Emile DeWeaver pointed out in his article “Moving the Needle on Black Liberation,” mass incarceration harms more Black people than police shootings. In 2017, the police killed 112 Black people but imprisoned nearly a million. People get lynched in “courtrooms around the country Monday – Friday,” raps Plies in his hit “100 Years.” Yet, as I watch my 15-inch flat screen TV from the top bunk of a 6 x 9 cell, I don’t see armies of protesters marching against the much larger problem of mass incarceration.

I believe we allowed mass incarceration to happen right in front of our faces because we lost sight that prisons contain people. We lost sight of the inhumanity of putting a 16-year-old in an adult maximum-security prison or sentencing a burglar to 66 years to life. We didn’t care about “inmates,” because we forgot they’re human beings.

Calling someone housed in a correction facility “a person in prison” or an “incarcerated person” is very different from calling him or her an “inmate.” If we use “person” as the noun and “incarcerated” as the adjective, we keep their humanity front and center.

We are people despite our mistakes. I’ve been in hundreds of prison self-help group sessions and heard the backstories of hundreds of men incarcerated for violent crimes. They all eventually took accountability for the harm they caused. Remorse drives many of them to help stop cycles of further violence. From hearing their backstories and studying behavioral science, I see their humanity and that they often committed crimes for really human reasons. When we call any of them “inmate,” we disconnect from the person and we don’t take accountability for our role in failing them before they made the decision that failed us.

Consider my own circumstances. Growing up, I was a nerd who attended Catholic schools from 1st grade through the 11th. I played video games on a Commodore 64 computer, rode a skateboard, collected Marvel comic books, watched Star Trek, played Dungeons & Dragons just like the guys in The Big Bang Theory.

However, I grew up in the New York City’s murder capital — Brownsville, Brooklyn. Being an awkward, extra-light-skinned kid was hell. I faced bullying daily. When bullied, when robbed, when beat up, I had three choices: endure physical harm, call the cops and face ridicule from the police and ostracism from my peers, or fight back. I chose to become pugnacious towards the oppression. Although I have always hated violence, I hated feeling helpless and being bullied even more. So, I fought my neighbor — for acceptance, for respect, and to be left alone.

Things accelerated when I was 17. A 16-year-old with a gun tried to rob me and my little brother. I refused to give up my gold ring; I ran, my little brother was shot. After that day, I started carrying a gun and using it when faced with similar circumstances. Fast forward to age 29, when two armed men were robbing my friend right before my eyes. I opened fire, killing one and wounding the other.

Today I realize that my real enemies weren’t my neighbors or the police. The real enemies were post-Jim Crow segregation accomplished through redlining, employment discrimination, policing policies rooted in maintaining white supremacy, gun show loopholes, addressing criminal behavior and addiction through violence, the lack of emotional intelligence education in the school-to-prison pipeline, felony disenfranchisement and untreated trauma.

My growth took place in prison. However, it wasn’t by design. I started my time in a maximum-security prison wanting help, but all they had was Narcotics Anonymous, Alcoholics Anonymous, Jesus, Buddha, and Mohammed. It took 13 years for me to reach San Quentin and get real help, real opportunities, and only by God’s grace did I make it here. I owe San Quentin for being a unique correctional facility that offers me unique opportunities. In the last seven years here, I’ve accomplished so much, including graduating from college, getting nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, effectively counseling kids through the SQUIRES program, creating a program empowering incarcerated artists, completing 10 self-help groups, and more. Yet some still call me an “inmate.” Good thing I know I’m not, or I would have wasted these last 20 years just mopping floors and getting face tattoos.

Rahsaan “New York” Thomas is the co-host and co-producer of the Pulitzer Prize-nominated podcast Ear Hustle, as well as a contributing writer for the Marshall Project and San Quentin News. He is currently incarcerated, and a legal campaign seeking help to secure his freedom can be found here.